The Global Slave Route

African Diaspora heritage is explored both internationally and nationally by academics, governments, non-governmental organizations and when done by community members, can indigenize the historical narrative. In recent years we have seen a proliferation of interest in cultural industries, places of memory, the digitization of traditional territory, genealogical studies, ethnobotanical research, built heritage, the recognition of intangible aspects of cultural expression and more importantly policy initiatives. Each subject matter enhances research, awareness, dissemination and nuances the interpretation and inclusion to the history narrative. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024) has galvanized each of these themes for inclusion “in national geographies and topographies…as one of the best ways of combatting omission, denial and distortion of the facts”. But how do we actualize this effort into metered and measurable progress for African-Diaspora studies in Suriname, South America? How do we use tangible historical evidence to bring cohesion to the experience of writing and promoting Maroon historical experience in Suriname?

The precursor to the UNESCO International Decade for People of African Descent was the UNESCO Slave Route (1994-2014) project. The aim of the Slave Route project was to present a macrocosm of the forced migration of African peoples to the far corners of the globe. From this purview the slave route project focused on: the fifteenth though seventeenth century African source countries used to supply human cargo for the slave trade; international routes and destinations hubs to the Americas, Europe, Middle East and Asia; and the end of slavery period in all relevant countries. The products of the Slave Route include not just knowledge and awareness about the locales related to slave hubs in various countries, but sites for preservation. In particular, as it contributes to the promotion of “memory tourism”.

However if we consider the term ‘slave route’ in its most literal sense we can see that slave routes were a phenomenon not just exogenous to a nation state but endogenous to countries with particularly dynamic environments. UNESCO’s Slave Route project, by virtue of the topic, is marred with all the historical atrocities of the slave trade and the act of servitude. The impetus behind the macrocosmic slave route is rooted in European agency for the explicit purpose of monetization. But what endogenous ‘routes’ were instrumental to the freedom of escaping slaves? Particularly as they led to the phenomenon of maroonage in numerous countries through the New World; Jamaica, Mexico, Cuba, Southeastern United States to name but a few. Of these countries which provided the opportunity for sustained maroonage, successful extrication from slavery and sustained freedom to embolden the formation of an identity in the midst of slavery’s constraints?

The history of Maroons has long been studied for its role in the creation of a distinct African Diaspora culture. Aspects of their tangible and intangible heritage have been researched for retentions in Africanisms and adaptations to New World encounters with colonial and Amerindian cultures. There is less focus on how they found their way from the plantation to freedom experienced in ancestral settlements deep in the jungles of South America. Maroon culture was created in part to the large flight of slaves from plantations to hidden enclaves in dense tropical forests, mountains and creek banks. But how did they get from the plantation to what would become an ancestral settlement? This paper will explore the formidable slave routes of Suriname and their role in creating Maroon culture. Further to the point we will consider how creating the historical narrative contributes to the institutionalization of Maroon heritage in Suriname.

The Maroon Slave Routes

Suriname Maroons reside in the largest swath of pristine rainforest in the world; an area which covers approximately 80% of Suriname’s undeveloped landmass in the District of Sipilawini. This geographical milieu comes with its own dynamic story. The six distinct groups of Maroons (Saramaka, Ndjuka, Paramaka, Kwinti, Matawai and Aluku) residing in vastly different regions of the hinterlands all meet the international definition of tribal peoples. The tribal peoples’ classification provided the legal impetus that led to 2007/2008 Organization of American States adjudication against the Government of Suriname for human and land rights violation to their tribal constituents. To this measure Suriname Maroons are defined by their social organization, autonomous habitation in the hinterland of Suriname, and distinct language and customs. The combination of these attributes differentiates Maroons from the larger Afro-Surinamese population and other historical Maroon communities in the New World.

Moreover, of the four hundred plus registered tangible heritage sites in Suriname only a handful are reported in Sipilawini. The lack of a robust heritage reporting can be interpreted to mean that Maroons and other inhabitants of the rainforest are without a historical link to a landscape they have traversed for hundreds of years.

From the Ground Up

The Kleine Commewijne River region in eastern Suriname provides us with a microcosm of how the historical literature, oral testimonial and existing tangible heritage is used to surmise where, why and how slaves traversed the forest.

A configuration of 17th – 18th century plantations located at the confluence of the Mapane, Kleine Commewijne and Tempati Creeks, near the cluster of the four villages Kawina[1] Maroons claim as their territory. In the late 1600s there were a little over a dozen plantations and by the mid to late 1700s that amount tripled. By the late 1600s the Commewijne River and its southward extending tributaries boasted an established plantation system with sugar as the primary product.

Kawina Maroons report colonial period tangible heritage sites along the Kleine Commewijne and Tempati Creeks, an area with no currently occupied villages. According to their oral history, their migration to the Tempati began from the Cordonpad and Jodensavanne plantations along the Powakka corridor. (GENERAL MAP SLIDE)

The plantations were established initially producing sugar. Types of large and fairly immovable tangible heritage found at Commewijne River sugar plantations include foundations, sugar mills and steam machinery. Smaller artifacts of European and Indigenous origin, including ceramic potsherds, green glass bottles, clear white medicine bottles and ceramic storage jars can also be found at plantations.

Aside from what we know from archival maps, there have been no structured ground assessments to identify plantation era tangible heritage in the area of Tempati and Kleine Commewijne Creeks. Therefore there is no archive of moveable and immovable tangible heritage that might still be visible on the ground surface.

By the early to mid-1700s the economic driver shifted from its primary product of sugar, to wood exploitation for timber needed to support a developing colony. This took place mainly along the tributaries of the Tempati and Kleine Commewijne Creeks. These new economic ventures did not stop long held resentment between colonists and escaped slaves. Throughout the mid to late 1700s on both Kleine Commewijne and Tempati Creeks there was guerilla warfare between the Maroon and Dutch colonials.

The 1757 uprising of five plantations on the Tempati Creek—La Paix, Bleyenburg, Maagdenburg, l’Hermitage, and Beerenburg marked the beginning of the end of the sugar plantation system along these creeks (KDV Architects 2004). The uprising culminated at the Oranibo plantation at the Pennenica Creek with the Dutch taking a last stance before withdrawing altogether from the Tempati and Kleine Commewijne Creeks. These series of events precipitated the signing of the 1760 peace treaties between the colonial Dutch and the Maroon groups. In October 1760 the Aucaneer (Ndjuka) Maroons were the first to sign a peace treaty with Dutch colonial government and the Saamaka Maroons followed in 1762. General terms of the peace treaties state: Maroons were to maintain several hours travel distance from the nearest post; permission was given to engage in trade of wood, cotton and livestock and collect in groups of no more than 50 at certain river banks.

In the time following the peace treaties the Kleine Commewijne and Tempati Creeks were used primarily for wood exploitation. A military post was established at Maagdenburg from which expeditions were launched to monitor and quell attacks by antagonist Maroons. Furthermore, Maagdenburg was reestablished as an infirmary and housed with medical specialists to treat ill Dutch soldiers recruited for the expeditions (Stedman 1791). From the late 1770s onward the Oranibo plantation also functioned as a military post working in tandem with the Maagdenburg post located in the heart of Maroon territory along the Tempati Creek (KDV Architects 2005).

It is unclear whether the uprising of Tempati slaves was instigated by Ndjuka Maroons from the Auca (Ndjuka formal name “Aucaneers”) plantation of the Suriname River and that the Tempati slaves then joined the Ndjuka group. Even though Kawina Maroons refer to themselves as an offshoot of Ndjuka it is also unclear at what point in time they began to refer to themselves as Kawina.

In the 18th through 19th century, traveling from Pondocreek (Sur-131 and Sur-132) near the Mapane Creek, escaped slaves traversed the Tempati Creek to settle at a series of locations, each within an hour’s travel and south of contemporary community forest plots. Beginning with Poitiede meaning white man’s head, this location is a Maroon and Dutch militia battle site located at a small waterfall in the creek. From Poitiede they travelled to Beekawe. The name is two part, Bee (planter’s name) and kawe (Ndjuka word meaning a place in the bush to go to). Mango trees, historic green glass bottles and earthenware ceramics can be found there. The next village in this cluster is Kondee, where a turnable post carved in a human form stands. The object, described as having two distinct sides, was turned from one side to another to convey messages about the whereabouts of descending white militias.

The area of Jacob is also mentioned by John Gabriel Stedman in his 1791 Narrative of an Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Suriname. The location is described as a timber cutting settlement used by Maroons. He offers no description of the group of Maroons residing in this location or the relationship of this place to travel distances to procure wood. Whether or not the Aucaneers Dorp referred to as Foto on the map can be attributed to one of the reported Kawina Ndjuka ancestral sites is not clear. What is clear is that there was recognized Ndjuka Maroon presence in this region in the 18th through 20th centuries; if not due to plantation uprisings, then for wood procurement. (See Slide of Tempati Creek map)

Members of the original Saamaka villages of Asigron, Dreipada and Balinggsula reported several locations of tangible heritage in or near their villages along the Suriname River. Inhabitants of Asigron claim historical territory up to and including Dreipada. Together they are the keepers of the local history and trace their migration from the upper courses of the Suriname River. Asigron is a transfer name from the Upper Suriname River area near the modern village of Langu. Dreipada, however was used as a boat landing and has a high sandy bank that does not easily flood.

Beetoyah was consistently reported by all three villages. It is the Samaaka pronunciation of the word Victoria and is reportedly located where Compagnie Creek meets the Suriname River. According to their oral history Beetoyah was an 18th century meeting place of slaves prior to it becoming a military post in the 19th century. Objects that can be found at Beetoyah include stone foundations remnants of the old military barracks. In addition the area is used as a burial site for Asigron persons. A similar slave gathering location was reported for Brokopondo Island, a land feature across from Brokopondo Centrum. This location provided respite for migrating slaves traveling from the upper courses of the Suriname River. The historic timeline when this took place could not be ascertained. (SLIDE with location of Brokopondo Island)

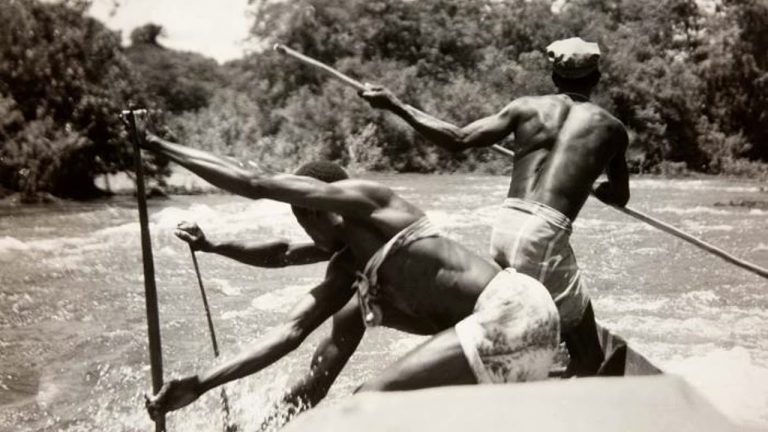

Sedukeke, was reported as a battle site and possible 18th century slave route accessible at Boslanti. It is held in spiritual regard by inhabitants of certain villages. Oral accounts suggest slaves arrived at Boslanti and crossed the river in order to continue their travels. Residents of Boslanti utilize a trail referred to as Herman’s Passi (Path) that extends into the forest and crosses Musa Road towards the tributaries of the Kleine Commewijne and Tempati Creeks. Ceramic objects may be found in the slave route creeks, but Maroon objects (boat paddles and wood carved objects) made of perishable material may not be discovered.

The so called slave route is not an open paved path or road. The community members know the route by land features such as creeks, hills and vegetation and track it by machete marks on trees; the result is a simple bush trail only experienced trackers can identify.

The example offered above is but one of many explanations that give an account of how one group of Maroons came to exist in a particular region of Suriname. And the archives and oral testimonials are a means for understanding the intricacies of how history can be revealed. The relationship of plantation rebellions to creek routes and Maroon ancestral settlements is but a means of discerning how, where and why certain groups of Maroons committed themselves to particular regions that would become what we know now to be their traditional territory.

However, the need to understand Maroon cultural heritage, and the benefits thereof, are not often linked with contemporary paradigms used to explain the circumstances of marginalized/ tribal peoples. So how is this relevant to UN Diaspora expectations; as we are now past the Slave Route project and in the early phase of the Decade of the Diaspora with objectives beyond mere historical factoids?

African Diaspora Heritage

Suriname—as is often the case in the discourse of African Diaspora research—presents the context to examine the effects of outmigration, ethnic disintegration, environmental degradation to traditional territory, poor socio-economic outlets and more importantly human and land rights violations. All of these themes have amassed into ‘issues’ regularly tackled by organizations with a directive to initiate some version of sustainable development programs to marginalized groups in Suriname. And in the context of the Suriname’s interior rainforest, Maroons are a highly marginalized group. Moreover, with only a smattering of basic level schools and clinics, this region is without viable inroads to job growth and upward social mobility. The set of circumstances means many Maroons are left to engage in illegal logging or illegal small scale mining with outcomes that lead to environmental hazard for the rainforest and their own traditional habitat. These issues, combined with a lack of national recognition for legal rights to land has left a community ripe for international support, ranging from World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International to Amazon Conservation Team, to name a few. Each organization has the mandate to assess and assist communities living below acceptable international metrics for health, education and access to essential services.

In the midst of implementation there is some version of heritage management. But understanding how Maroon communities define and manage their own heritage in the midst of changing political climate is not often a consideration. Looking forward it may be beneficial to consider how we might better be able to bridge the unique experience—via collaborative and cross-disciplinary research—of Surinamese Maroon ancestral settlements with similar historical occurrences throughout the New World.

Indigenizing Heritage Management

The idea of indigenizing Maroon heritage management simply means that policies, institutions must be better educated about the role of these groups in the maintenance and perpetuation of their culture.

Indigenized Heritage explores themes of Amerindian and European cultural sharing and appropriation, creative methods for identifying and exploring African Diaspora ancestral sites in neotropical zones, the enduring themes of retention, rebellion and resistance of African traditions in Atlantic World and the politicization of African Diaspora communities.

The concept was born from years of experience and challenges exploring African Diaspora archaeology in Suriname in addition to witnessing the growth of the subject throughout South America, the US and Caribbean.

Indigenized Heritage is the means by which traditional heritage research, interpretation and dissemination is contextualized and reproduced by and for groups of descendant communities, indigenous peoples, tribal groups often marginalized in the wider discourse of historical and cultural transformation in the colonial period.

Our mission is to understand the intricate relationship African Diaspora peoples had with their Amerindian and European counterparts in the Atlantic World during the dynamic period of colonialism. In addition we wish to synergize the intellectual trajectory expressed in theory, methodology and data of African Diaspora archaeology across the Atlantic World.

What is our Goal

The goal is to identify, document, research and manage the archaeological heritage of African Diaspora communities in Suriname and throughout the Atlantic World.

- We explore the overlap of

- We approach Indigenized archaeological heritage with the intent of researching and revealing a range of archaeological resources such as ancestral settlements, fortifications, migratory patterns, artifact assemblages and battle sites, to mention a few.

- In addition we seek to better enable indigenized communities to practice sustainable heritage management.

How do we accomplish our objectives? By applying cross disciplinary methods at the academic and community levels. We take a mixed method approach to integrate students with community based needs that incorporate archaeology, archival documents, ethnography, oral history, ecosystem services, geology, the use of information and communications technology and more importantly, community engagement to train and build capacity to conduct videography, oral history interviews, research design and museum exhibits and material culture stewardship for sustainable heritage management. Via these methods we seek to broaden and deepen the knowledge and discourse of cultures indigenized in the Atlantic World.

Saramaka Maroon Community Heritage

This discussion highlights the vital role anthropologists have played in negotiating issues of heritage management in the recent Inter-American Court of Human Rights’(IACHR) decision regarding the rights of Saramaka Maroons to ancestral land that was destroyed without the acknowledgement, authority or agreement of Saramaka peoples. The Saramaka, a tribal group living in Suriname, accused the Surinamese government of allowing multi-national logging enterprises to harvest timber from traditional Saramaka territory. In addition to this violation of human rights, the government did not provide a plan following the destruction of Saramaka collective property. In response, the Association of Saramaka Authorities submitted a petition to the Inter-American Commission claiming the government of Suriname did not consider the socio-cultural character, and the subsistence and spiritual relationship the Saramaka have with their environmental heritage. The IACHR judgment1 arms the Saramaka with the legal underpinning to enact a heritage management strategy to safeguard their physical and cultural survival.

Extensive anthropological research has been conducted among the Saramaka that further demarcates their distinctive cultural patterns (Herskovits 1936; Price and Price 1980). Their major cultural features assert that they are politically and socially autonomous river based communities with an egalitarian social structure and a hunter and gatherer subsistence economy (Figure 2). They practice a mild form of slash and burn horticulture and have numerous rituals that reaffirm their relationship to their natural environment and their ancestors, including a matrilineal descent order and matrilocal housing schemes. In addition, archaeological evidence suggests that during the Maroons’ formative period they benefited from the technological advancements of neighboring indigenous peoples (Ngwenyama 2007). The cultural information about Saramaka Maroons provided by anthropological research contextualizes their social relevance within the larger Surinamese national identity. Maroon history and the corresponding anthropological research foster the recognition of Maroon cultural identity on an international level.

According to the criteria of UN Convention No. 169 (1991 Convention), Maroons fall under the legal rubric of tribal peoples. The term Maroons derives from the original Spanish term cimarrone, describing loose cattle, is used by academics to describe former enslaved Africans that aggressively claimed freedom to live in autonomous communities. Even though the Saramaka were one of the first Maroon groups to sign a peace treaty with their Dutch colonial counterpart in the 1760s—to determine the stipulations concerning privileges to land and all the benefits thereof —the Saramaka have been the victims of blatant disregard to violations of the Maroon treaty and of Convention No. 169.

The violations have been in the form of the construction of a hydroelectric dam which encompasses numerous Saramaka villages and mining and logging concessions granted to multinational companies. Both cases are seen as an affront to the quality of life in traditional Maroon territory by destroying homes and provision grounds in the Upper Suriname River Basin.

The hydroelectric dam was built by Surinamese domestic authorities in the 1960s as a power source for the mining industry and the growing population in coastal Paramaribo (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname). During the construction process, Saramaka villages were flooded and displaced to so-called “transmigration villages” the likes of which were merely shanty dwellings without the cultural character and availability of subsistence provisions provided in a traditional Saramaka village (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname Article III A 12).

According to the Saramaka, construction of the dam has fostered persistent negative effects on Saramaka cultural territory (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname). Moreover, the timber exploitation of the 1990s only exacerbated an already sordid situation. According to a 2001 press release, “The Saramaka leaders first became aware that a concession had been granted in their territory when a group of ‘Englishspeaking Chinese’…arrived in the communities and informed the communities of Saramaka that they were about to begin logging operations” (Forest Peoples Programme 2001). Awareness of the logging concessions, enacted without collective Saramaka approval and consent, prompted them to take legal strides to address the issue. The dam construction and the timber extraction permanently destroyed hamlets of extended families and their shared sub subsistence plots. Saramakaans affected by both these events were forced to migrate to the capital, Paramaribo, where many work as unskilled laborers and exist in urban squalor.

The case began in Oct. 27, 2000 when after much deliberation, Saramaka Maroon right to determine the use and access of communal property was defaulted by the Surinamese government. Prior to this date three formal complaints were presented to the Surinamese government, each met with no response. Writing about their unsuccessful attempts to seek justice legally, Fergus MacKay (2003:3) writes that the Saramaka ”concluded that Surinamese law was so stacked against them that resort[ing] to the courts would be futile, offering them no possibility of success [because] Surinamese law vests ownership of all unencumbered land and resources in the state, there are no environmental laws and Indigenous and Maroon rights are not in any way legally guaranteed” (MacKay 2003:3). In response the Saramaka formed a grass-roots organization called The Association of Saramaka Authorities (Figure 3). With the legal backing of international lawyers of the United Kingdom based Forest Peoples Programme, the Saramaka petitioned to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights about alleged violations to their traditional culture on the Upper Suriname River region. In an acknowledgement of this petition (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname Article I 2 [2007]) the IACHR found that the Surinamese government violated Article 3 ‘Right to Juridicial Personality’ of the Convention by “failing to recognize the legal personality of the Saramaka people”. The Saramaka supported this accusation with a catalog of issues stemming from the building of the dam, presented to the Surinamese government in 2003.

The grievances calcified into recurring issues which the government of Suriname repudiated based on perceived inaccuracies in the Saramaka petition. Surinamese national polities argued the petition stemmed from the Saramaka’s lack of understanding of Surinamese judicial prudence. The government furthered this point by stating that Saramaka use of the land is a privilege not a right. The Saramaka addressed the government allegations by counter stating that the system of Saramaka land tenure is based on clan ownership or lo (in Saramaka language). The government of Suriname did eventually acknowledge that their judicial system did not recognize the right of Saramaka peoples to use and enjoy property in accordance with their cultural system of communal ownership (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname [2007]).

Validating Saramaka Cultural Identity

The foundation of the Saramaka case was based on illustrating a uniquely Saramaka Maroon cultural construct and validating their cultural autonomy within the larger Surinamese national identity. In order to accomplish this goal the tribe had to prove that the Saramaka essentially are who they say they are—a tribal people born of colonial hegemony, but socially removed from contemporaneous Surinamese nationals. The role of anthropological science in a case such was relegated to the validation process, because it addresses the obvious regarding how the Saramaka illustrate who they are, their lifestyle, and manifest variables of culture that differentiate them from their Indigenous and Creole Surinamese neighbors. Once these issues were addressed, the question arose of whether their difference warranted specified treatment. To demonstrate their social difference cultural anthropologist Richard Price, an expert on Maroon developmental history and cultural behavioral, was asked to submit “expert evidence” to the Inter-Commission on Human Rights illustrating the cultural nuances of the Saramaka people.

Price’s defining publications on Saramaka social structure were produced in the seventies after several intense years of ethnographic research in the sixties with his wife, Sally Price. Richard Price’s sole publications —Saramaka Social Structure: An analysis of a Maroon society in Surinam (1975); First-Time: the historical vision of an Afro-American people (1983a) and To Sly the Hydra: Dutch Colonial Perspectives on the Saramaka Wars (1983b), and their joint effort Afro-American Arts of the Suriname Rainforest (1980) are frequently cited in regards to cultural matters concerning Maroons of the Guianas, in particular Saramaka. Richard Price’s report states why the Saramaka are a unique cultural entity that complements the definition of UN Convention 169. The testimony (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname Article VI A 65f [2007]) presented the grist of the cultural evidence needed to validate Saramaka traditional lifeways.

Charateristics of these lifeways include the use of an azonpow, a wooden frame, elevated and horizontally placed at the entrance of a village. The azonpow indicates that a village is non-Christian and adheres to traditional ritual practices. Entrance to a traditional village is also marked by gender specific paths. Though there are spatial differences within villages all Saramakaans along the Suriname River valley practice the Koyo celebration. The Koyo event is a village wide celebration of menses and marks the beginning of womanhood. Young women are paraded around the village and donned with the traditional panghi garb. During menses women are sequestered to menstrual houses along the periphery of the village. Women are disengaged from social and domestic activity and are not allowed to wash in the river where food preparation and the washing of eating utensils typically take place. Some women seek greater freedom of movement by relocating themselves to a secluded and removed place along the riverbank.

To support his statement, Price offered and explained a cultural map created via the participatory geographic information system (PGIS) method by Saramakaans with funds from the Forest Peoples Programme (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname Article VII F144 [2007]). The Saramaka cultural map demarcates dwellings, ancestral land, provision plots, places of spiritual and ritual significance, and the location of subsistence items such as fish, fowl, game, and vegetation for medicinal use and timber used for dwelling construction. This entire body of evidence created a basis from which the Association of Saramaka Authorities and their legal representation from the Forest Peoples Programme were able to compile and condense validation of a tribal identity.

Richard Price’s anthropological testimony was dismissed by Surinamese legal polities as outdated accounts of a culture long transformed by larger national issues—notably independence from the Netherlands in the mid-1970s and a civil war in the 1980s. The 1975 change of power was a precursor to the financial and social instability that set the stage for civil war through the 1980s. Independence brought with it a development assistance program signed with the Holland to enhance infrastructure. However, the inability of the then new government to properly institute development benefiting all Surinamese quickly offset a military coup d’etat in 1980. The civil war was fueled by the recruitment of Maroons from various regions of the country that interpreted their social circumstances in Suriname’s hinterlands as disenfranchisement from infrastructural and social inroads enjoyed by the larger Surinamese population. In this context, Maroons such as the Saramaka became likely candidates for acts of civil unrest. These events had transpired since the Price’s initial research and surreptitiously affected the migration of large amounts of Maroons from forest hamlets to city dwellings. This migration was essentially seen as forcing the Saramaka to acculturate into a larger national milieu of amorphous cultural identities.

This discussion not only constructs awareness of the heritage of a tribal people, but also, underscores the role of anthropology as a tool for mediating international issues in heritage management in environmentally contested spaces. African Diaspora heritage is at the front line of international discourses on human rights violations—a position that necessitates the integration of different types of anthropological methodologies. Ethnographic data coupled with archaeological evidence about the material continuity of the Saramaka may have better illustrated the relationship they hold with their ancestral community (Figure 4). For example, the best available archaeological evidence that we have tells us that there is continuity of cultural practices in the form of Maroon ceramics (Ngwenyama 2007). The ceramics speak to the spiritual relationships Saramaka have with their environment. Saramaka ancestral history is rooted in associative places. Forest creeks are named for eventful historical migrations and ancestral figures, and noted areas along the river banks mark historical battles with Dutch colonists. In addition, the ceramic vessels are a reflection of ceremonial spiritual preparation of ancestral Saramakaans prior to battles. Ceremonial ceramic vessels called ahgbangs can be found in prayer schrines strategically located in contemporary Sarmaka villages (Ngwenyama 2007; White 2009). This archaeological data that I have compiled is evidence of strategically placed ahgbangs used for ceremonial washing at an early 18th century ancestral settlement named, Kumako. According to oral historical accounts and historical records, Kumako was the site of a defining battle between the Saramaka and Dutch planters. Evidence of similar use and placement of ahgbangs can be found among other contemporary Maroon groups throughout Suriname. But according to Richard Price’s (1983a) compilation of oral historical accounts it is the Saramaka that used ahgbangs to mix powerful vegetation to permit the magic of invisibility from colonial enemies. This knowledge was passed to ancestral Saramakaan from Indigenous peoples during the formative years of Maroon migration. A further interpretation of contemporary ceremonial washing from the ahgbang is to address social illness on the individual and /or familial level in order to appease avenging ancestral spirits (Ngwenyama 2007: 194).

The accounts discussed above demonstrate the marriage of ethnographic and archaeological methods in order to grasp the indiosyncratic nature of culture as it is expressed socially and materially at ancestral places. By combining these two anthropological methods we can further bolster an argument for cultural continuity and legitimize the contemporary use, relevance and meaning of ancestral places.

Heritage Management From Within

The judgment of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights was the culmination of a seven-year case against the government of Suriname in which anthropological testimony provided information outlining the cultural markers of Saramaka Maroons, thereby validating their right to a traditional lifestyle. Because of the stipulations outlined by the judgment, anthropology can move out of the academic sphere and become a practical and useful tool for mediating environmental heritage matters such as the case of the Maroons.

How does understanding the value of different types of anthropological methods in a situation such as this translate into sustainable heritage management in Suriname? The decision of the Inter-American Court provides a legal rubric for Suriname Maroons to maintain and preserve their cultural and environmental heritage. Reparations defined in the judgment mandates the following:

That environmental and social impact assessments are conducted… prior to any development or investment project within traditional Saramaka territory, and implement adequate safeguards and mechanisms in order to minimize the damaging effects such projects may have upon the social, economic and cultural survival of the Saramaka people. (IACHR Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname Article VIII C.1 194e [2007])

More importantly, the reparation justifies Maroon need for a heritage management infrastructure. Developing a sustainable anthropological archaeology program in Suriname that will arm Maroons with the means of securing their environmental and cultural rights offers a solution by 1) working with Maroons in the pursuit of their legal right to communal ancestral property; 2) curating and exhibiting key Maroon material culture at local institutions; and 3) providing training in anthropology and archaeology. This will enable documentation of Maroon environmental heritage as they negotiate their cultural transformation on an international stage. By creating this type of infrastructure, tribal peoples such as Maroons, can control their cultural identity.

The Maroons received a prestigious form of reinforcement for their activities when key figures of the Association of Saramaka Authorities, Wanze Eduards and Hugo Jabini, became one of six recipients of the 2009 Goldman Environmental Prize for grassroots environmental action, representing Central of South America (The Goldman Environmental Prize 2009). The Goldman Prize is hailed as the Nobel Prize of environmentalism, and acknowledges the tireless efforts of the Association of Saramaka Authorities throughout the lengthy Inter-American Court of Human Rights Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname 2007. The international recognition associated with receiving the Goldman Prize places greater accountability on the Surinamese government to adhere to the IACHR mandate that “free, prior and informed consent [by Saramakaans] be required for major development projects throughout the Americas” (The Goldman Environmental Prize 2009). Receipt of such a prestigious award further demonstrates how the knowledge provided by anthropologists can affect how government policy mitigates the preservation of cultural heritage.

In sum, archaeology was not apart of the court case, and material culture only a slight part of the argument.Yet I believe based on my own research among Maroons that multiple methodologies can and should be part of discussions about heritage management here and elsewhere. The policy outlined in the case regarding applied social science will hereafter be at the forefront of the Saramaka decision making process. This will pave the way for multiple methods to be used in future, notably archaeological, assessments prior to development projects that can cause permanent landscape damage. The mandate creates a platform from which anthropologists may develop heritage management programs and responses that are more conducive to addressing social issues as they effect the cultural transformation of African-Diaspora communities.

Contributing to the Slave Route Discourse

The examples offered above are but a dose of Suriname’s history. One which is dynamic and often not a part of national decision making discussions about identity, culture and cultural place. As with the Saramaka example we see that cultural place and identity had no previous place in government dialogue. It is no wonder why African Diaspora identity was then forced in the space of international legal dialogue.

The Slave Route project as it is actualized recognizes already determined aspects of African Diaspora heritage as decided upon by national bodies, not necessarily by the peoples that lived the history. What of the nuanced history within a nation state that goes beyond the colonially defined cultural spaces. The idea of what a slave route is may need a different representation; one from the ground up that redefines the term. In the context of Maroonage here in Suriname and other countries with a strong Maroon history, a slave route is and should be recognized as the path to freedom beyond just colonial waterfront enclaves. Maroons came to be precisely because they created their own slave route. One which still remains in the collective memory of contemporary communities and celebrated in oral historical accounts and recognition of ancestral settlements, battles sites and locations of ritual practices.

References:

Fermin, Philip.

1781 [1778]. Historical and Political View of the Present and Ancient State of the Colony of Suriname in South America; with The Settlements of Demerary and Issequibo; together with an account of its produce for 25 years past. London: W. Nicoll.

Forest Peoples Programme

2001 Surinam Maroons say no to multinational logging. World Rainforest Movement. Forest Peoples Program Press Release. Electronic Document, http://www.wedderwille.de/Bilder/Suriname_2001/fpp02.htm, accessed January 1, 2003.

Heilbron, W. and Willemsen, G.

1980 Goud en balata-exploitatie in Suriname: nieuwe productie-sectoren en nieuwe vormen van afhankelijkheid in: Caraibisch Forum nr 1, jaargang 1 en nr 2, jaargang 1.

KDV Architects

2003 [2007].Suikerplantage Breukelerwaard aan de boven-Commewijne. Retrieved from, http://kdvarchitects.com/smartcms/default7987.html?contentID=1.

2004 [2012]. de plantages aan de Tempati. Retrieved from http://kdvarchitects.com/smartcms/default7987.html?contentID=1.

2005 [2009]. Suikerplantage Oranibo aan de boven-Commewijne. Retrieved from, http://kdvarchitects.com/smartcms/default7987.html?contentID=1.

- Houtgrond Victoria aan de Surinamerivier. Retrieved from, http://kdvarchitects.com/smartcms/default7987.html?contentID=1

Hester, T.R., Shafer, H. J., & Feder, K. L.

1997 Field Methods in Archaeology 7th Edition. Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Herskovits, Melville J.

1936 Suriname folk-lore. New York: Columbia University Press.

MacKay, Fergus

2003 Logging and Tribal Rights in Suriname. World Rainforest Movement. Electronic Document, http://www.wrm.org.uy/countries/Surinam/logging.html, accessed January 1, 2003.

Ngwenyama, Cheryl

2007 Material Beginnings of the Saramaka Maroons: An Archaeological Investigation. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida.

Price, Richard

1975 [1974] Saramaka Social Structure: An analysis of a Maroon society in Surinam.

Caribbean Monograph Series, No.12, Institute of Caribbean Studies. Puerto Rico: University of Puerto Rico.

1983a First-Time: the historical vision of an Afro-American people. Johns Hopkins

studies in Atlantic history and culture. Richard Price, ed. Baltimore: The John

Hopkins University Press.

1983b To Sly the Hydra: Dutch Colonial Perspectives on the Saramaka Wars. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers.

Price, Richard and Sally Price

1980 Afro-American Arts of the Suriname Rainforest. Berkeley: University of California Press.

The General Conference of the International Labour Organisation .

1991 Convention (No. 169) concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries. Electronic Document, http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/62.htm, accessed March 13, 2008

The Goldman Environmental Prize

2009 The Goldman Environmental Prize 2009 Recipients. Electronic Document, http://www.goldmanprize.org/recipients/current, accessed April 20, 2009.

White, Cheryl

2009a Archaeological Investigation of Suriname Maroon Ancestral Communities. Archaeology and Material Culture Issue, Caribbean Quarterly 55:2.

2009b Saramaka Maroon Community Environmental Heritage. Practicing Anthropology 31(3): 45-49.

[1] Kawina are an offshoot of the larger and better known Ndjuka Maroon tribe.

/s3/static.nrc.nl/images/raster/071213wet_aukaners.png)

/s3/static.nrc.nl/images/gn4/stripped/data21579561-b55fc3.jpg)